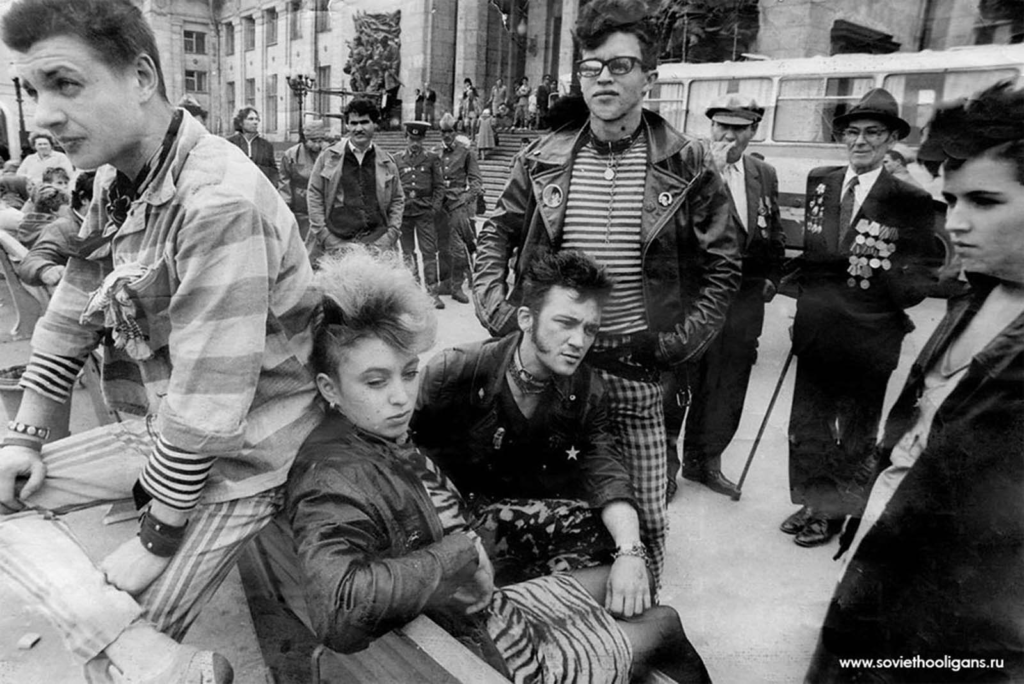

The subcultures in the Soviet Union, a country cut off from the West by the infamous Iron Curtain, were a form of open youth rebellion against ideological and cultural stagnation.

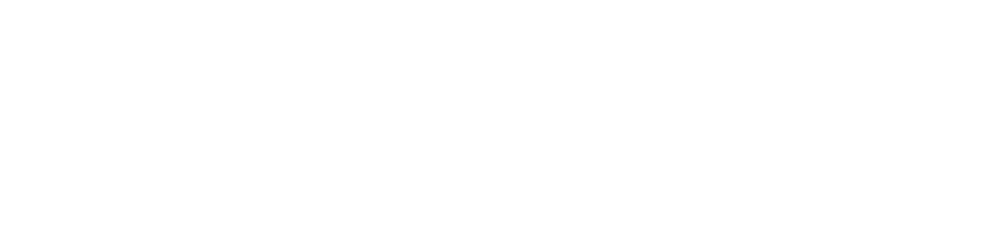

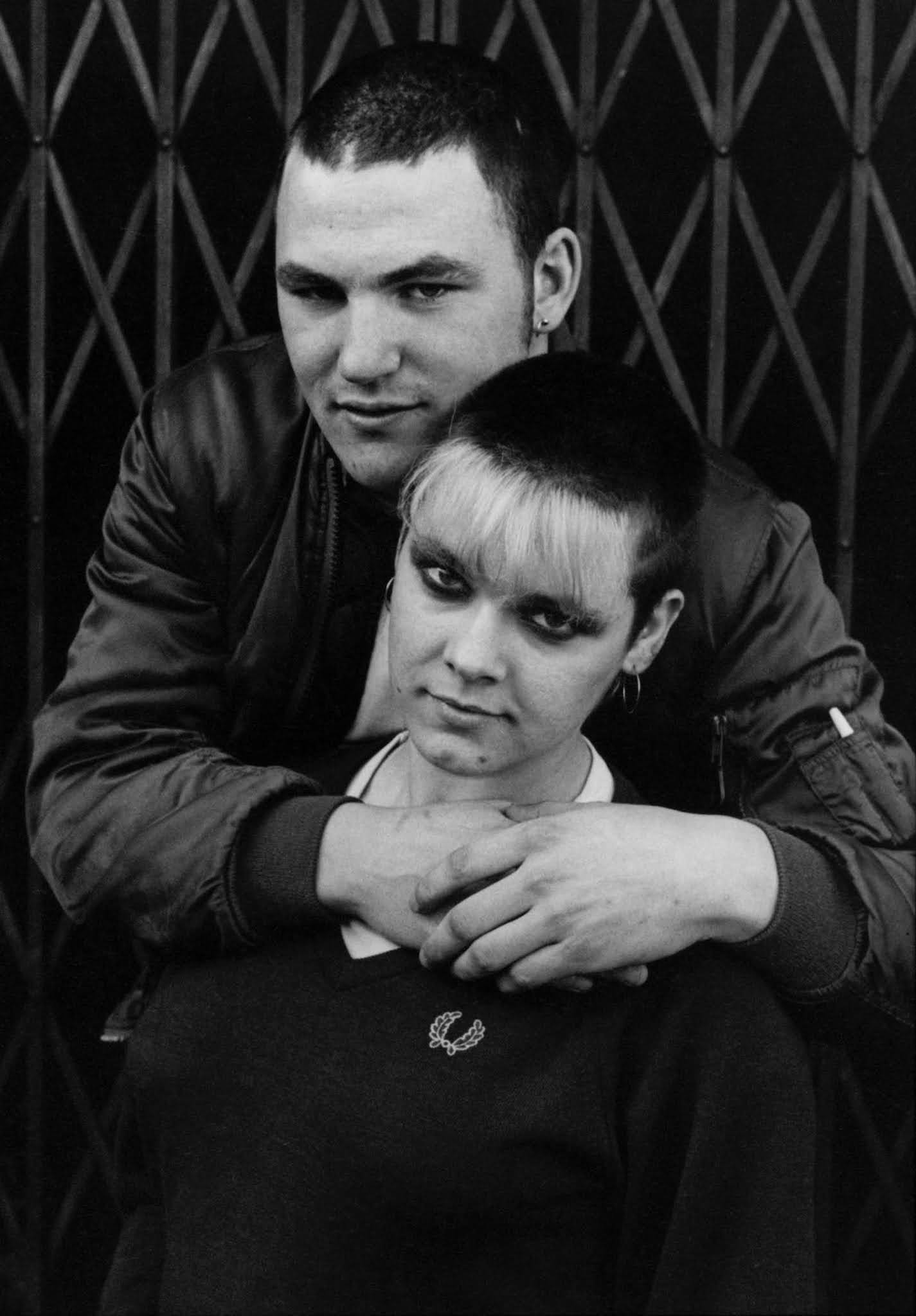

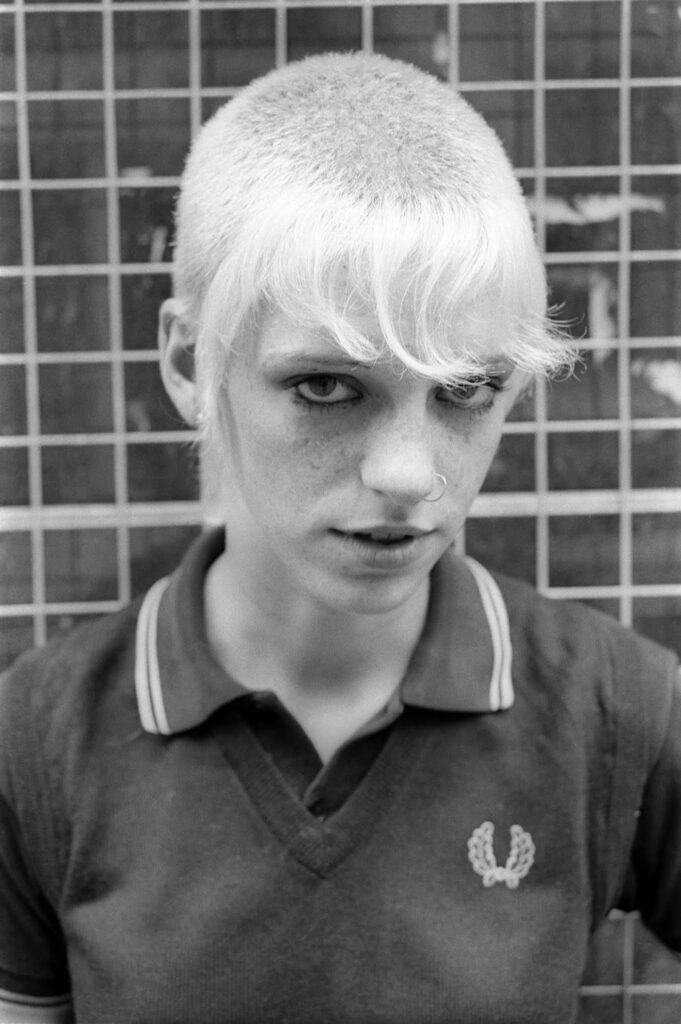

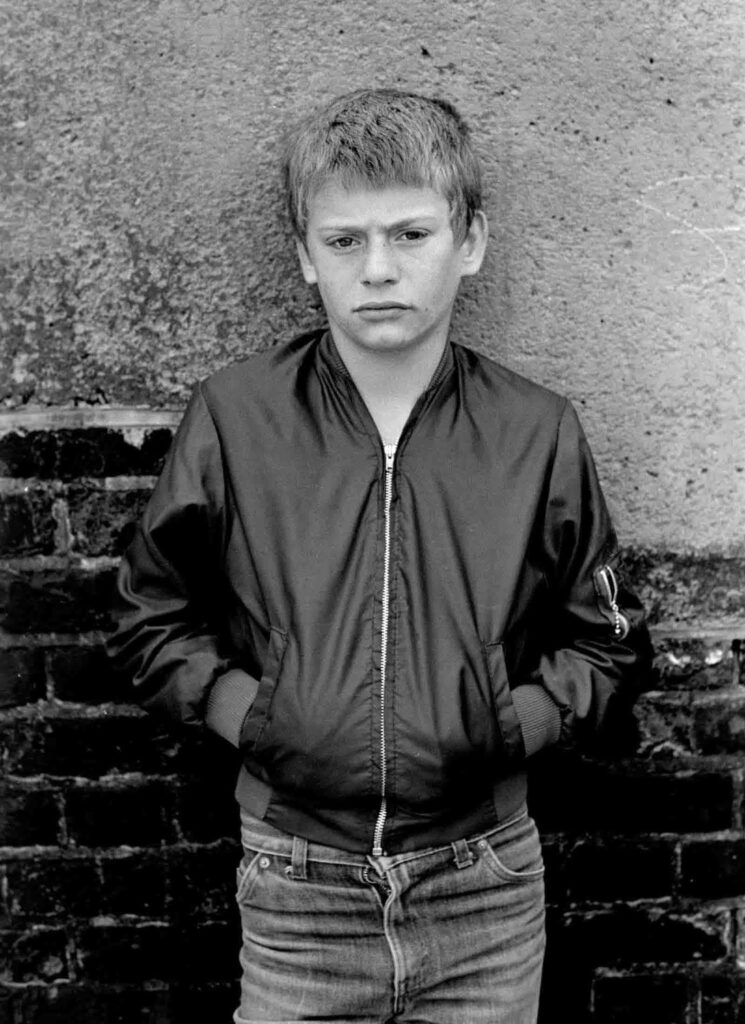

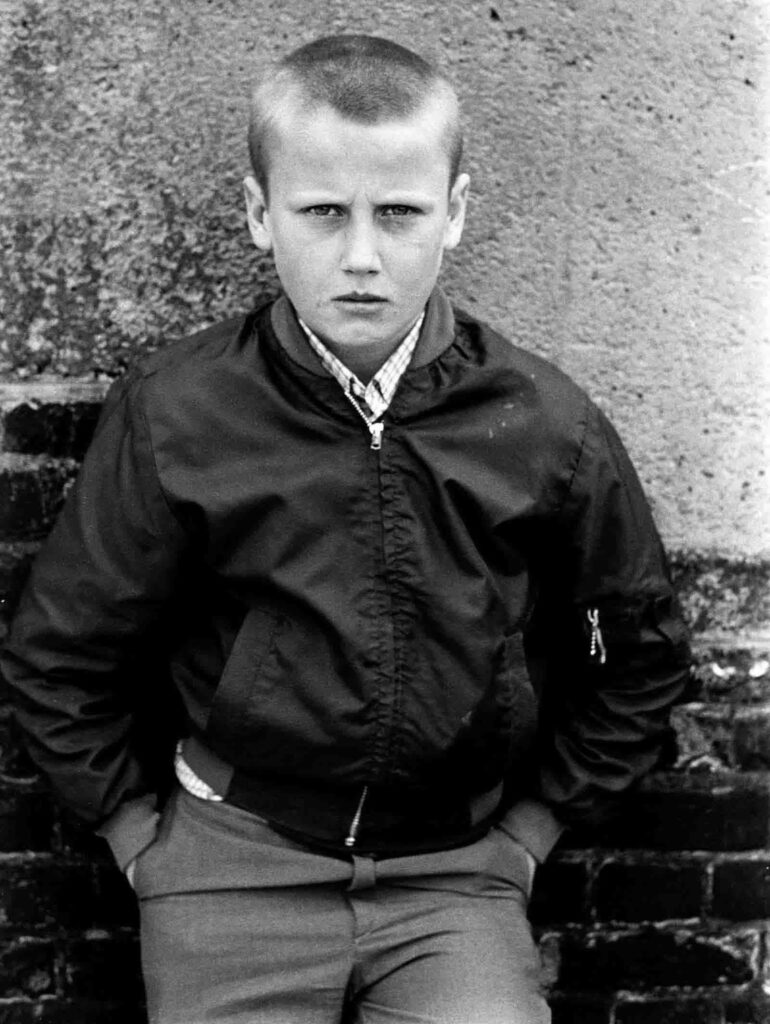

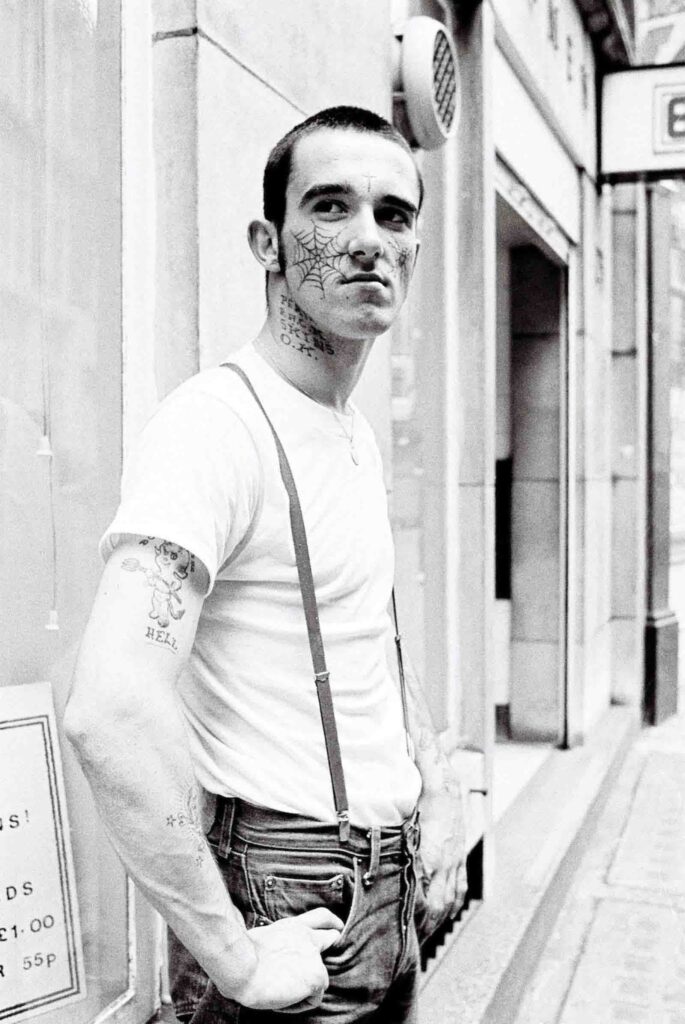

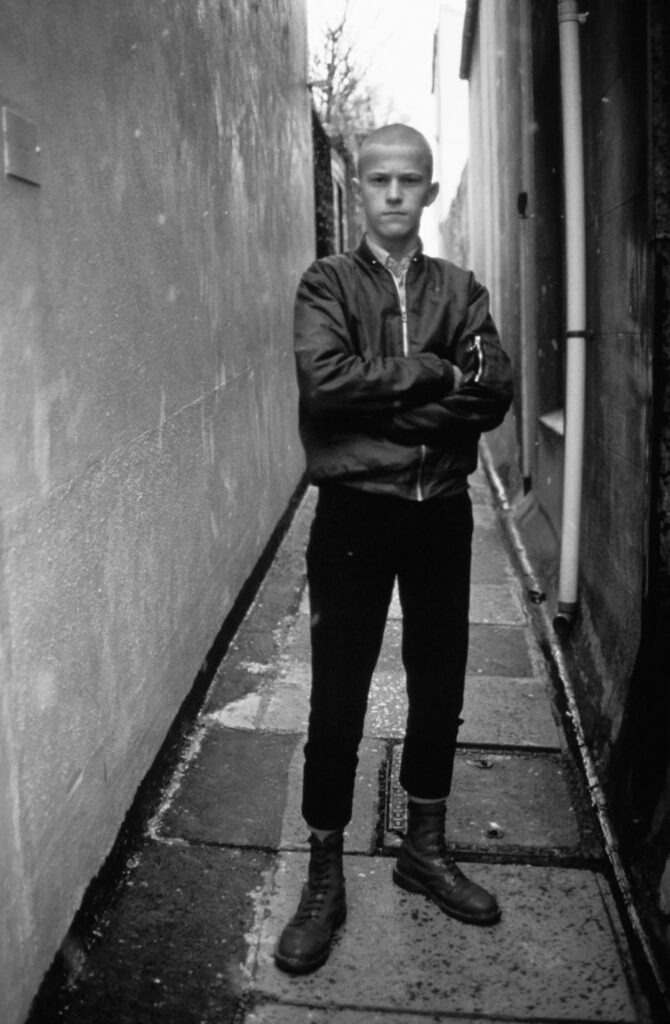

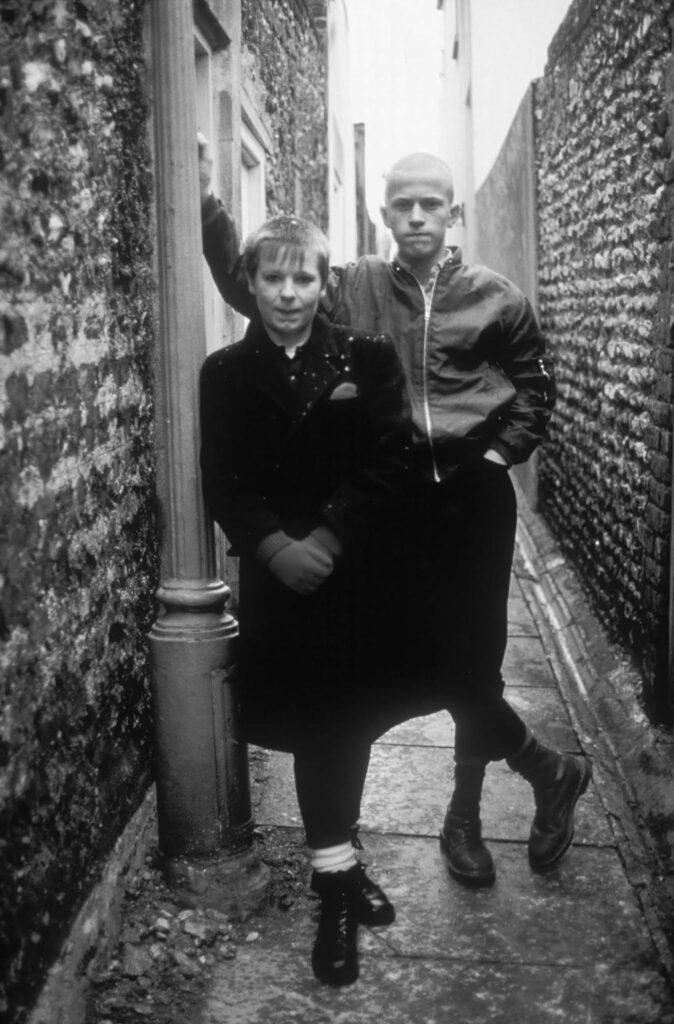

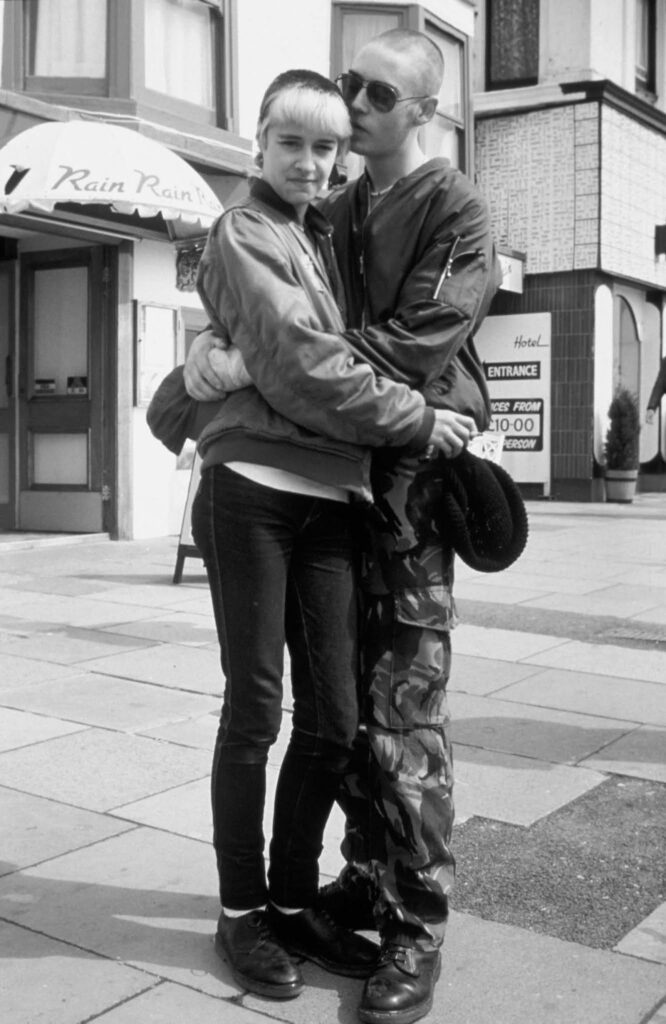

Stilyagi, goths, hippies, bikers, punks, rockers, and metalheads formed countercultures that often invited the wrath of the Soviet communist authorities. Their legacy is remembered by these pictures that show their radical self-expression, extravagant style, hairstyles, tattoos, and elaborate clothes.

The Soviet state media called these groups “non-conformists,” who were deliberately devoid of all the good qualities possessed by a Soviet citizen. They were even referred to as lazy parasites, dirty, leeches of society, and fascists.

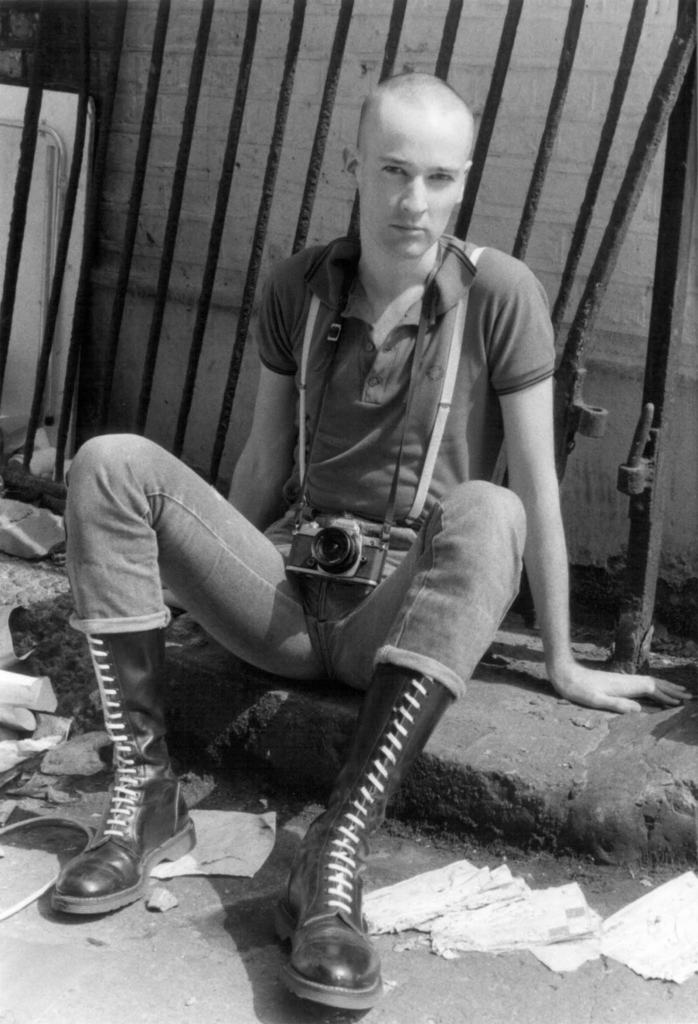

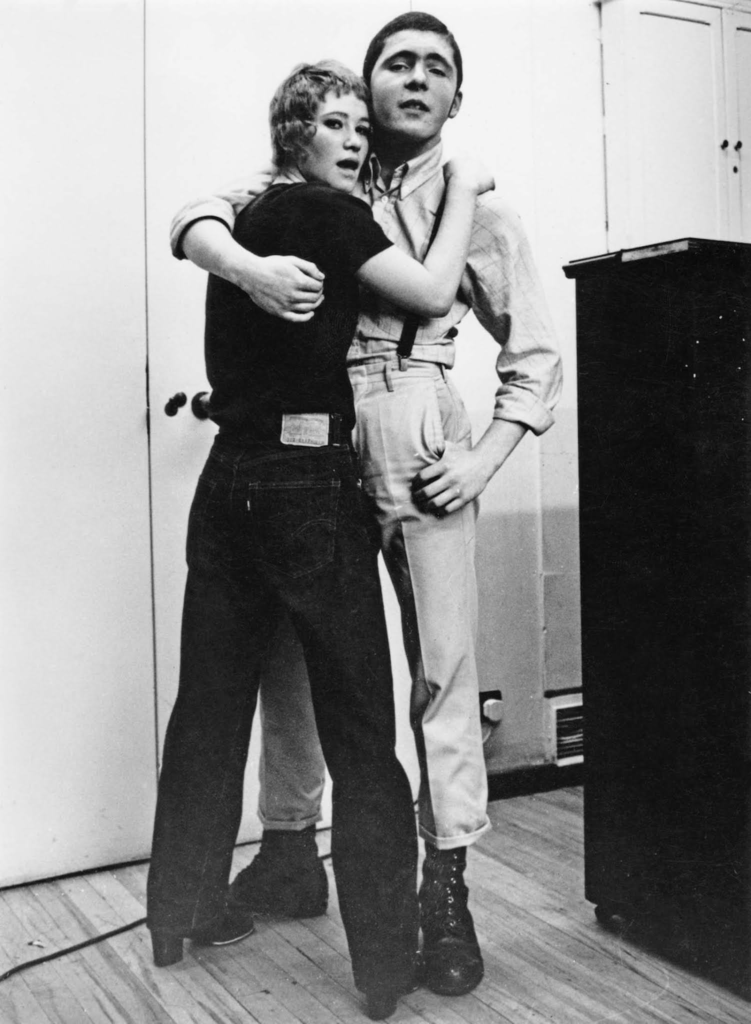

A stilyagi was primarily distinguished by snappy clothing—preferably foreign-label, acquired from fartsovshchiks—that contrasted with the communist realities of the time, and their fascination with zagranitsa, modern Western music, and fashions corresponding to that of the Beat Generation. English writings on Soviet culture variously translated the derogatory term as “dandies”, “fashionistas”, “beatniks”, “hipsters”, “zoot suiters”, etc.

Stilyagi greatly favored swing and boogie-woogie. Women wore dresses and high-heeled footwear, while men chose narrow checkered pants and shiny winkle-pickers. Though their style changed a bit over time, the Stilyagi always wore unapologetically bold colors and bright jackets.

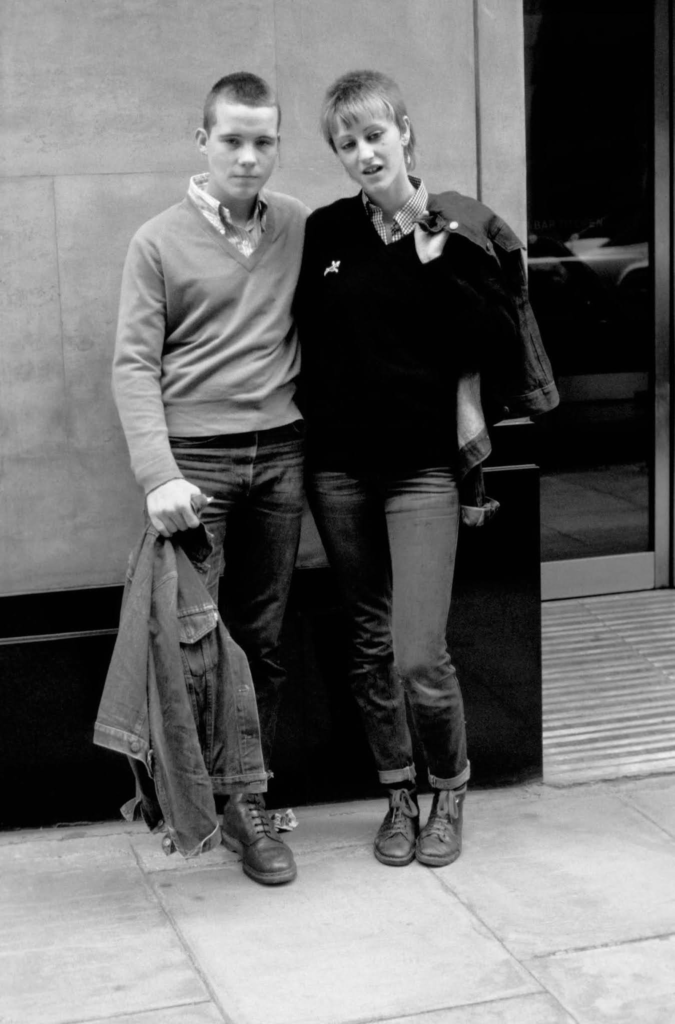

The factors motivating Soviet hippies were subtly different than those experienced by their American counterparts. While American hippies rebelled against what they saw as a decadent and corrupt consumer culture in which they were forced to participate, Soviet hippies turned against a state that surrounded them with enforced conformity.

Hippies in the Soviet Union were stereotyped, arrested at concerts, and hassled for their drug use and Western values. But by turning to an international youth movement, they proved that East and West had plenty in common, long before the Iron Curtain fell.

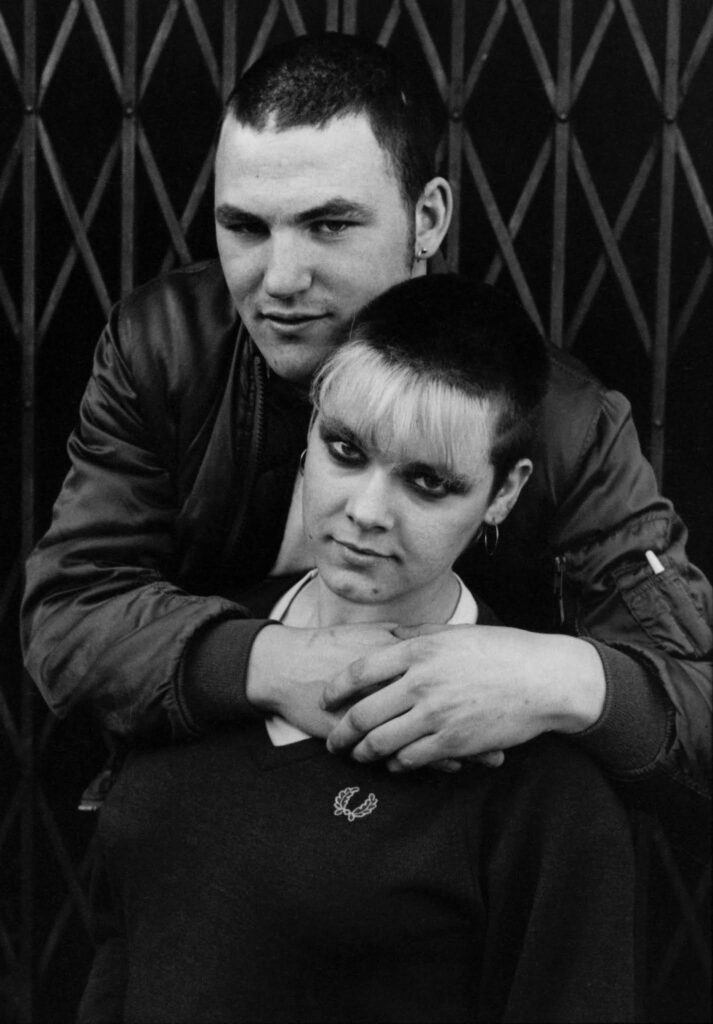

In the late 1980s, Sektor Gaza formed, reaching cult status. They created a genre called “Kolkhoz punk”, which mixed elements from village life into punk music.

Another cult band that started a few years later was Korol i Shut, introducing horror punk, using costumes and lyrics in the form of tales and fables. Korol i Shut became one of the best-selling and most highly regarded bands in the history of Russian Rock.

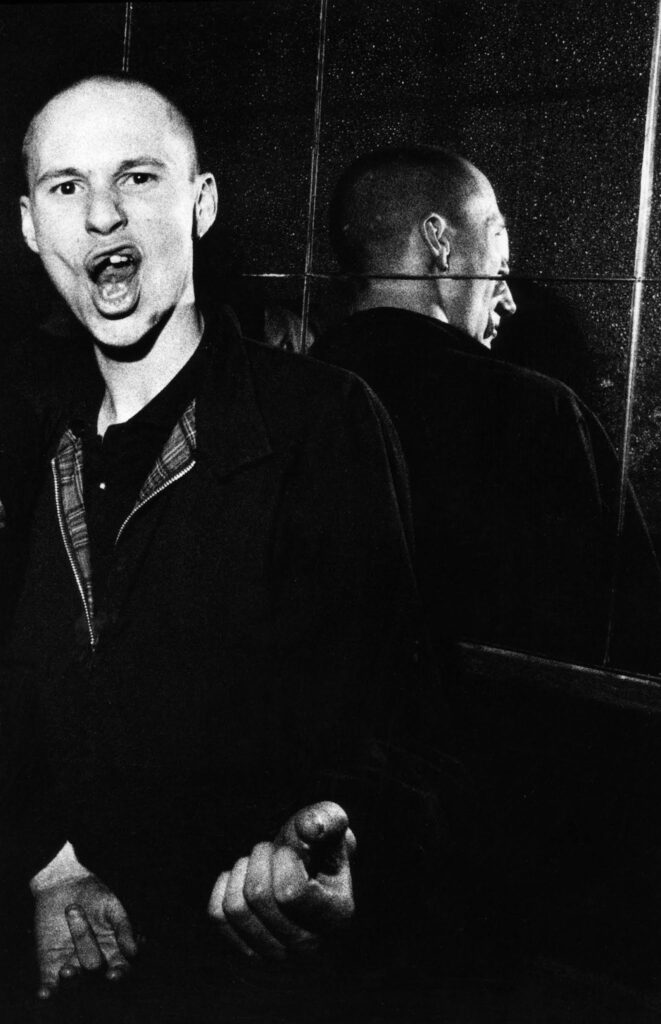

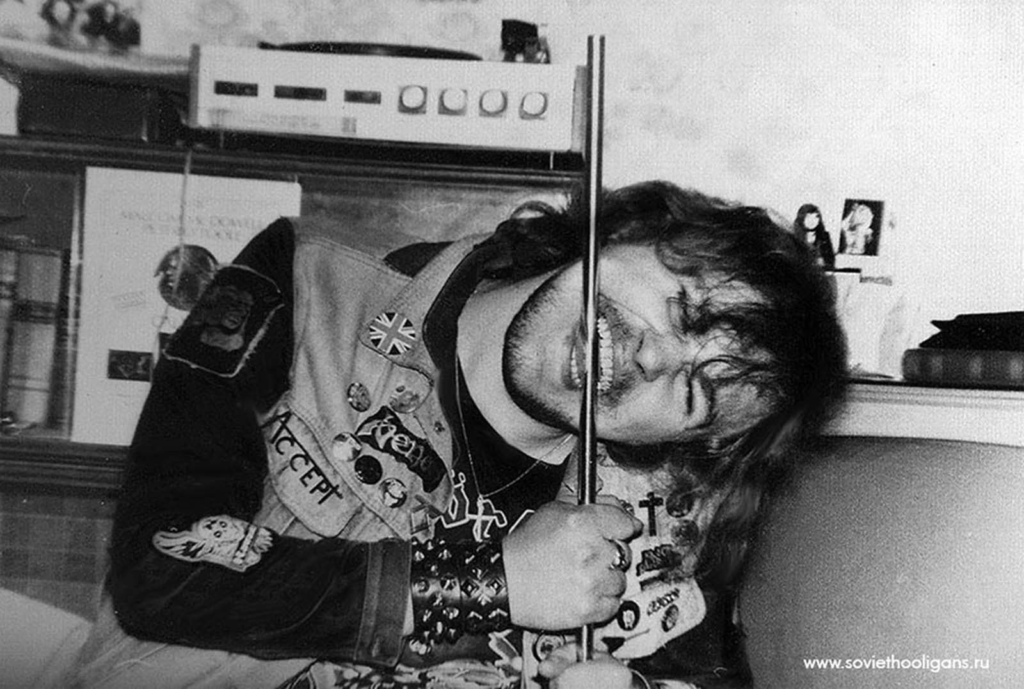

With banned foreign music growing in popularity, alternative genres, including heavy metal, became a fad among young Soviet citizens. Heavy metal bands like Black Sabbath, Iron Maiden, Metallica, Judas Priest, and Megadeth were popular among the rebellious Soviet youth. The followers were labeled as metalheads.

Soviet rockers usually gathered in the evening on weekends, generally somewhere close to parks or other public spaces. They liked riding through the sleepy streets at night and thus became a subject of acute police interest. At the same time, police motorcycles were often outdated and quite often could not keep up with bikers.