What was punk – and why did it scare people so much?

A man in punk dress is apparently admonished by a man in London in the mid-1980s. Punk’s expressive dress and anarchic politics were seen as a general affront to middle English conservatism in the mid-1970s, with the movement continuing as a subculture through the 1980s and beyond.

PHOTOGRAPH BY ROGER HUTCHINGS / ALAMY

EVERYONE knows the sound of punk: unfiltered and breathless, an assault of sonic claustrophobia captured unpolished in a studio, or garage, living room, or perhaps an alleyway. Guitar riffs are sharp and unruly, driven by drums clattering around a gritty, decisive bassline. Vocals are unpolished and expressive, yelling lyrics loaded with agenda above the instruments. Aggression, frustration, sneering sarcasm – and all of it loud.

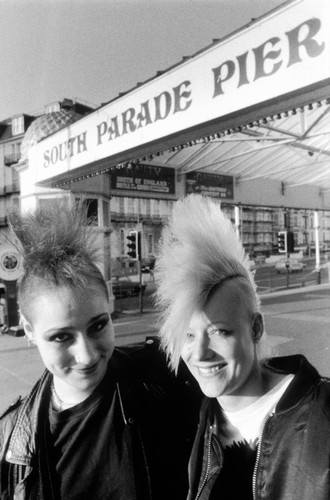

Everyone too knows the look of punk: statement haircuts, ripped clothing, badges, metalwork, makeup and leather. To its makers and its audience, punk was the cultural identity of anger, disenfranchisement, and rebellion.

The surge of – and appetite for – the punk scene in the late 1970s and early 1980s wasn’t limited purely to the music. It became an ideology, spawning literature, poetry, fashion and political defiance. But, as dramatised in new Disney+ biopic Pistol, it was the music that became its gravitation point, giving a beat and an identity to a genre that would explode, implode – and be reinvented over the decades around the world. (The Walt Disney Company is majority owner of National Geographic Partners.)

Defining the undefinable

Punk as a movement – perhaps appropriately – defies definition. Defined by Monika Sklar in her book Punk Style, punk was a ‘vital new way to perform subcultural ideas, that incorporated its own art, music, dress and lifestyles… commonly rooted in those who are somehow disenfranchised from society.”

The word punk was originally an archaic term for a prostitute – ‘Puncke’ was used by Shakespeare as such in Measure by Measure, though ambiguously – and was later a common slang term for any kind of miscreant, or charismatic, good-for-nothing threat to authority such as the characters played by James Dean or Marlon Brando in movies such as Rebel Without a Cause and The Wild One. It was also widely used as prison slang to denote a victim of predatory sexual advances.

People in punk dress walk down King’s Road in London in the 1970s.

PHOTOGRAPH BY HOMER SYKES / ALAMY

Exactly when it was appended to music is uncertain, though it’s likely to have been a lot earlier than most realise. A note in the San Francisco Call of 3 October 1899 carried the outraged remarks of one Otto Wise, who reviewed the singing of a companion in a fraternity house as “the most punk song ever heard in a hall.” In this and later tuneful contexts, which were plentiful, the word was used as an adjective to describe any kind of music that was authentically ragtag or unpolished – the implication being that those making it were somewhat rough around the edges as well.

Far from a simple expression of alternative ideas, or music simply of a lowbrow nature, by the time ‘punk rock’ was a thing, it was perceived as being on a mission to deliberately provoke. Miriam-Webster defined the music as “marked by extreme and often deliberately offensive expressions of alienation and social discontent” – though the word wasn’t used widely when the movement was first finding its voice. It was around, though: In the May 1971 edition of edgy music magazine Creem, journalist Dave Marsh, in a retrospective of 1960s US bands ? and The Mysterions, described their output as being a “landmark exposition of punk rock” – one of the first times the term was coined as a genre.

The Sex Pistols in the United States, 1978. Punk rock grew concurrently in the U.S. and the U.K., though the musical movement began in America with bands such as the New York Dolls and The Stooges helping set the scene for what would follow. Stooges songs were part of the repertoire of the Sex Pistols.

PHOTOGRAPH BY PICTORIAL PRESS LTD / ALAMY

American groups such as the New York Dolls and the Ramones (‘New York rock’), The Stooges and the MC5 in Detroit (‘garage rock’) had the swagger and bare-bones musicality vibe nailed. But the general use of a term so associated with scallywags of one kind or another was frowned upon, and mainly used by journalists to categorise elements of their music. A 1976 article in the UK’s Sounds magazine by John Ingham was entitled ‘Welcome to the (?) Rock Special’ – the question mark a clear statement that nobody quite knew what to call the new movement now emerging in the U.S., Australia and in the U.K. On the eastern side of the Atlantic at least, punk rock didn’t get its enduring identity until there was a band of suitably shameless menace upon which to pin it.

Trigger point

Enter the Sex Pistols. The mid 1970s punk scene in the UK came at a point of economic decline and civil unrest. A recession was in full swing, police were clashing with the public on the streets in a series of disputes, Britain was sliding down the economic power list and – against a backdrop of a fading, increasingly costly Empire – the prospects for young people were bleak. An ungovernable ‘failed state,’ as summed up by journalist Simon Jenkins, who wrote: “The word ‘strike’ was in every page of every newspaper almost every day. Public services really were collapsing. This country really was a mess.”

The Sex Pistols performing in Norway, 1977. The band used European dates to emphasise their ‘banned in the UK’ notoriety, though in truth the band was never banned; merely their songs were excluded from the playlist of conservative broadcasters like the BBC, which it is believed limited their commercial success. Many believe the controversial single ‘God Save the Queen’ reached number 1 in the singles chart but was denied the accolade, losing out to Rod Stewart’s ‘I don’t want to talk about it.’

PHOTOGRAPH BY NORWAY NATIONAL ARCHIVES

Against such a scene, by the mid-1970s the emergence of a colourful counter-culture of bands that seemed to articulate the country’s frustrations were a tempting lightning rod for disenfranchised youngsters.

Punk rock’s musicality – or as perceived in some quarters, lack thereof – was itself a reaction. While artistically, the songs sometimes sounded like the band had only a loose acquaintance with their instruments (a 1973 review of The New York Dolls compared the sound of the band to lawnmowers) it was a conscious riposte to grandiose, stadium-filling bands playing rambling prog-rock and employing operatic and indulgent performances.

Punk rock, when it arrived, was edgy, brief and unpolished, with unpredictable and chaotic live performances which sometimes ignited pent up crowds into violence. Out went virtuoso solos and twinkly stagecraft: musicianship came second to attitude, and the feeling of accessibility – that those on stage weren’t couched and pampered rock stars, but just someone with struggles, frustrations and something to say. Lyrics were often politicised or critical of what was increasingly seen as a country run by arcane and regressive institutions.

Such rough but charismatic sound also bred its own recession-proof fashion. The ascetic, unkempt look of American rock bands such as The Ramones and Television and artists such as Lou Reed and Patti Smith – ripped jeans held together with safety pins, recycled thrift store clothes and t-shirts – spread across the Atlantic and became individualistic styles that were by definition a unique statement. While aped – ironically – by fans, the emerging movement provided a platform for self-expression that was authentic, rag-tag, and accessible for anyone.

Some of the boldest statements were crafted by Vivienne Westwood, who at the time was in a relationship with socialite and sometime promoter Malcolm McLaren. After the latter had spent a period in the U.S. managing the New York Dolls, he became interested in managing a local band called The Strand, which he and Westwood used as a kind of musical billboard for their Chelsea fashion boutique. With the rise in popularity of fetish wear, Westwood and McLaren had renamed the boutique from Too Fast To Live, Too Young To Die to SEX – and The Strand to the Sex Pistols, with McLaren describing his desired aesthetic for the band as ‘sexy young assassins.’

‘The antithesis of humankind’

It was an uncomfortable contradiction that success and popularity was the inverse to punk’s philosophy, but also the inevitable consequence of connection with large numbers of disenfranchised record buyers. This came to a scandalous head in December 1976 when Thames TV presenter Bill Grundy – who, in a last-minute switch, found himself interviewing The Sex Pistols instead of Queen in a primetime evening broadcast – appeared to challenge the band on its anti-materialistic authenticity given it had accepted £40,000 for a record deal.

Singer John Lydon, aka Johnny Rotten, mumbled a swearword under his breath which Grundy asked him to repeat in defiance of the channel’s stringent policies. After more goading, guitarist Steve Jones broke into a profanity-loaded rant at the presenter, all of which was broadcast live. Grundy’s career never recovered, and the Sex Pistols were instantly notorious.

Left:

Westwood and McLaren’s shop on The King’s Road in 1976. Initially named Let it Rock, then Too Fast To Live Too Young To Die, then SEX – and later The Seditionaries, and finally World’s End, which it remains to this day.

PHOTOGRAPH BY TRINITY MIRROR / MIRRORPIX / ALAMY

Right:

Malcolm McLaren and Vivienne Westwood in London, 1977. Westwood wears the original artwork for God Save the Queen on her t-shirst. Westwood’s designs were deliberately intended to shock and provoke, and she and McLaren’s influence over the Sex Pistols made them a leading charge on both the genre’s music and look.

PHOTOGRAPH BY TRINITY MIRROR / MIRRORPIX / ALAMY

Bernard Partridge, a member of the Great London Council, described the band as the ‘antithesis of humankind,’ adding that punk rock in general was “nauseating, disgusting, degrading, ghastly, sleazy, prurient, voyeuristic and generally nauseating… I think most of these groups would be vastly improved by sudden death.”

Anarchy in the UK

The perceived threat that punk rock presented to society was framed neatly by the release of what would become an anti-establishment anthem. For a target, as the head of state presiding over a country enduring austerity, the Queen was apparently as good as any.

Though the band denied the record was intended as a stunt, the Sex Pistols’ God Save the Queen was engineered by McLaren to be released during the Queen’s silver Jubilee on 27th May 1977.

Originally promoted using as a portrait of the Queen with a safety pin through her lip and with a record sleeve depicting ransom-like lettering over her eyes and mouth, the song – not unreasonably – was seen as an assault on the royal family and its values. Outlawed by the BBC, it was a popular success but also made the band targets for pro-monarchy supporters. Drummer Paul Cook was attacked outside a tube station by six men armed with knives; John Lydon was assaulted with razorblades outside a pub in Highbury leaving him with injuries to his hand and face.

The sleeve for the single God Save the Queen (1977.) The song was originally called No Future, and variations of the artwork, designed by artist Jamie Reid, included images of the Queen with a safety pin through her lip and swastikas over her eyes.

PHOTOGRAPH BY ROBERT LAZENBY / ALAMY

Lydon – who wrote the lyrics – has held the opinion that the song, which was originally titled No Future, was misunderstood. In Isle of Noises, Lydon told author Daniel Rachel the song captured ”the idea of being angry, of the indifference of the Queen to the population and the aloofness and indifference to us as people.” But writing in The Times in 2022, he stated: “I’ve got no animosity against any one of the royal family. Never did. It’s the institution of it that bothers me and the assumption that I’m to pay for that.”

45 years after its release, a reissue of the song reached number 1 in the UK charts for the first time on 4th June 2022 – the weekend of the Queen’s Platinum jubilee.

The inherent provocativeness of punk’s anti-establishment, anti-capitalism and anti-conformist statements inevitably went into darker territory, which deepened the divide between the older, more conservative generation and the punks themselves. As cultural theorist Dick Hebdige wrote in Subculture: The Meaning of Style, “No subculture has sought with more grim determination than the punks to detach itself from the taken-for-granted landscape of normalised forms, nor to bring down upon itself such vehement disapproval.”

Violence was a feature of many punk gigs – both within the crowd, between the crowd and the band, and between the more strait-laced public spoiling for a fight with a subculture seen as a genuine threat to the British way of life. Despite a reputation for unruliness, the punks became targets, too.

“Punk rock is nauseating, disgusting, degrading, ghastly, sleazy, prurient, voyeuristic and generally nauseating… I think most of these groups would be vastly improved by sudden death.”

“Punks’ transgressive, shocking attitudes and stances caused normative culture to react viciously against them,” wrote Andrew H. Carroll in ‘Running Riot’: Violence and British Punk Communities, 1975-1984, “and it further isolated them from normative society; the reactions against them pushed punks deeper into their alternative community.”

Another theory for punk’s perceived aggression was the spiralling divorce rate and the dissolution of what many considered ‘traditional’ family values. As Connell states, “one way young people reacted to this was by constructing a new community, centred on punk music, that used violence to define itself.”

In addition, sinister accessories such as dog chains and knives were adopted as effects. In a further shock attack on older generations swastikas and other Nazi aesthetics were frequently worn as a deliberate provocation to those who had fought in WWII three decades earlier.

The latter was infamously sported by John Richie – better known by stage name Sid Vicious – who joined the Sex Pistols as a bassist in 1977. Vicious would come to epitomise punk’s more self-destructive side: allegedly talentless as a musician, he became a heroin addict, assaulted members of the band’s audience, carved slogans into his chest on stage and in 1978 was arrested for the second-degree murder of his girlfriend Nancy Spungen in the aftermath of a party in New York. Vicious died from a drug overdose whilst awaiting trial in February 1979.

The Sex Pistols sign a record deal, 1977. Manager Malcolm McLaren (second from right) orchestrated stunts such as this for maximum publicity and affront to institutions such as the monarchy. It’s no accident the contract was signed in front of Buckingham Palace, nor that the record God Save the Queen was released to coincide with the Queen’s silver jubilee. The band themselves denied the record was timed as such.

PHOTOGRAPH BY PA IMAGES / ALAMY

Sid Vicious and Nancy Spungen in 1978. Both would be dead a year later Spungen supposedly at the hands of Vicious, and Vicious by a drug overdose. As Vicious died whilst awaiting trial, the question over who murdered Spungen – she was found stabbed by Vicious’s knife in late 1978 while the latter was in a drug-induced blackout – remains controversial.

PHOTOGRAPH BY PICTORIAL PRESS LTD / ALAMY

Punk goes mainstream

Vicious’s death was considered one of the death knells for punk itself. Bands that followed The Sex Pistols’ lead included Buzzcocks, The Damned and The Slits, all of whom were influential in developing punk rock as a genre along various political themes, from austerity to equality, with some – including The Clash – becoming highly successful in the process. The latter made racial tension one of its protest flags, after lead singer Joe Strummer witnessed the violence between police and Black revellers at the Notting Hill Carnival in 1976, penning the song White Riot in response.

The Clash, pictured here in 1979, would be one of the British bands that would develop punk rock beyond the 1970s.

PHOTOGRAPH BY PICTORIAL PRESS LTD / ALAMY

As the 1970s became the 1980s, punk became even more resplendent. But as the decade progressed, inflation fell, the economy improved and new, less volatile bands caught the attention of younger generations.

While less menacing and gritty, the bright colours, creative hairstyles and use of makeup and other more tranquil ostentations of the 1980s music fashion appeared a natural development of punk. But stylistically, many of the bands that followed were an exaggerated contrast to their predecessors. Artists influenced by the punk movement such as Duran Duran, Spandau Ballet, Siouxsie and the Banshees and Adam and the Ants earned the early nickname ‘peacock punks.’ The anger quelled, the motivations became less aggressive; guitars were augmented by new technology such as synthesisers that once again gave songs the produced shimmer bands like the Sex Pistols had gleefully binned. Punk, as a subculture, remained – but popular music evolved.

Their philosophy, however, didn’t – and has emerged periodically since, with movements such as gothic rock, grunge and EMO exhibiting many of the anarchic attributes that led to punk. Some of the albums produced in that first wave frequently rank in critics’ lists of the top albums of all time.

One of the bands identified as a kind of spiritual heir to The Sex Pistols emerged from Seattle in 1987. But for the lead singer, it was the philosophy, not the music, that tied the two together. “The only reason I might agree with people calling our band “The Sex Pistols of the 90s” is that, for both bands, the music is a very natural thing, very sincere,” said Kurt Cobain, of Nirvana. “All the hype the Sex Pistols had was totally deserved – they deserved everything they got.”

![A Scuttler gang [photo: Greater Manchester Police Museum]](https://www.bbc.co.uk/manchester/content/images/2008/10/20/scuttlers_470_470x200.jpg)