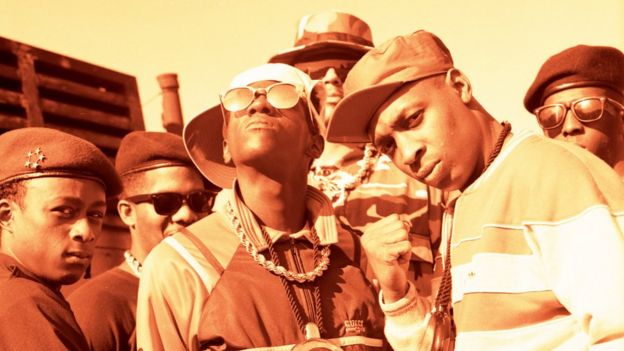

When Public Enemy frontman Chuck D was introduced to the righteous punk of The Clash, he didn’t get it.

“I thought they were a bunch of people with brand new music that were whining about their existence,” he tells the BBC.

“I didn’t think their problems were as severe as black people’s problems, but oppression is oppression and abuse is abuse.

“At that age I didn’t know how much their pain was. I do now.”

What the rapper later discovered was a band who were unafraid to take artistic chances, filing front-line reports on the poverty, boredom and lack of opportunity facing the British working class.

Fiery and idealistic, their music nonetheless seemed alien to a hip-hop fan in Long Island… until Chuck D’s friend Bill Stephney told him Public Enemy should be the rap equivalent of The Clash.

“The idea was that we were going to do something that would have a level of intellectual heft,” Stephney later recalled.

“It would have some substance to it, but it had to rock the party.”

The song that first made Chuck D “pay attention” to The Clash was The Magnificent Seven – unsurprising, given that it was itself inspired by the boombox rap of Grandmaster Flash and the Sugarhill Gang.

Built around a loping bass line (played by Norman Watt-Roy of the Blockheads) it saw Joe Strummer pick apart the human cost of capitalism, as he chronicled a day in the life of a minimum wage supermarket employee.

The combination of rap and a social message made a big impression; and Chuck cannily noted that reporters often talked about The Clash’s message as much as their music.

“They talked about important subjects, so therefore journalists printed what they said, which was very pointed,” he told NBC earlier this year.

“We took that from the Clash, because we were very similar in that regard. Public Enemy just did it 10 years later.”

Musically, Public Enemy were just as revolutionary, with cacophonous soundscapes that relied on avant-garde cut and paste techniques, brutal beats and the squeal of police sirens.

But of all the qualities they shared with The Clash – from attitude and lyrical urgency to musical innovation – Chuck says the most important was “fearlessness”.

Both bands fought for social and racial justice, and both faced criticism for their depictions of police brutality: The Clash on Know Your Rights and Public Enemy on Fight The Power.

But they remained staunchly, defiantly independent – even though, in The Clash’s case, they were signed to (and in some cases strait-jacketed by) a major international record label.

Chuck D suggests that most modern acts lack that spirit.

“Bands today want to sell out,” he says. “They’re not pressured to stay broke and unknown and unpopular.

“They want to be popular and known and able to make a living… so it’s hard to tell young people to stand up for something and not worry about being paid.

“And who can blame them? As you grow up, you gotta work. They want to be able to do their music and art and make a living at it and you gotta honour that.”

If you think the firebrand rapper sounds like he’s mellowing out, you’d be right.

Whereas once he declared: “Elvis was a hero to most / But he never meant [expletive] to me,” the 58-year-old no longer agrees with The Clash’s 1977 manifesto, “No Elvis, no Beatles or Rolling Stones”.

“Time has erased the golden idols and the only thing that fights against time is the proper curation of their works,” he says, presumably with one eye on his own legacy.

His own contribution to preserving The Clash’s legacy comes in an eight-part podcast, produced by Spotify and BBC Studios, which follows the punk heroes from their origins at the 1976 Notting Hill riots, to their clashes with the National Front, their struggle for creative control and their later experiments in funk, jazz, reggae and dub.

“It’s the story of a band that changed everything,” he says.

“They taught us to fight for what really matters – and to do it as loud as hell.”

Stay Free: The Story of The Clash is available now on Spotify.

Check out Subcultz event, The Great Skinhead Reunion Brighton