The Miyuki-zoku: Japan’s First Ivy Rebels

The first Japanese to adopt elements of the Ivy League Look were a youth tribe called the Miyuki-zoku, who suddenly appeared in the summer of 1964. The group’s name came from their storefront loitering on Miyuki Street in the upscale Ginza shopping neighborhood (the suffix “zoku” means subculture or social group). The Miyuki-zoku were mostly in their late teens, a mix of guys and girls, likely numbering around 700 at the trend’s peak. Since they were students, they would arrive in Ginza wearing school uniforms and have to change in to their trendy duds in cramped café bathrooms.

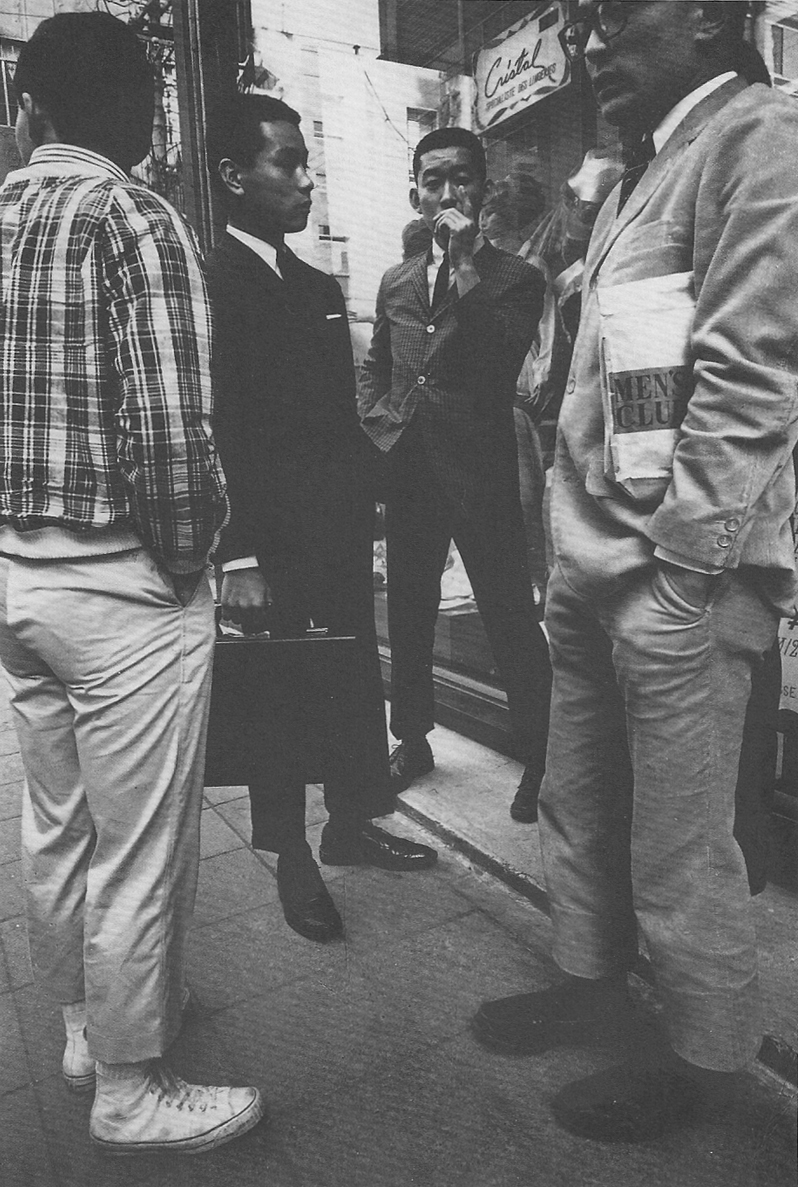

And what duds they were. The Miyuki-zoku were devotees of classic American collegiate style. The uniform was button-down oxford cloth shirts, madras plaid, high-water trousers in khaki and white, penny loafers, and three-button suit jackets. Everything was extremely slim. The guys wore their hair in an exact seven-three part, which was new for Japan. They were also famous for carrying around their school uniforms inside of rolled-up brown paper grocery bags.

What lead to the sudden arrival of the Miyuki-zoku? Although Japanese teens had been looking to America since 1945 for style inspiration, these particular youth were not copying Princeton or Columbia students directly. In fact, Japanese kids at this time rarely got a chance to see Americans other than the ever-present US soldiers.

The Miyuki-zoku had found the Ivy look through a new magazine called Heibon Punch. The periodical was targeted to Japan’s growing number of wealthy urban youth, and part of its editorial mission was to tell kids how to dress. The editors advocated the Ivy League Look, which at the time was basically only available in the form of domestic brand VAN. Kensuke Ishizu of VAN had discovered the look in the 1950s and pushed it as an alternative to the slightly thuggish big-shouldered, high-waisted, mismatched jacket-and-pants look that dominated Japanese men’s style throughout the 1950s. As an imported look, Ivy League fashion felt cutting-edge and sophisticated to Tokyo teens, and this fit perfectly with Heibon Punch‘s mission of giving Baby Boomers a style of their own.

When the magazine arrived in the spring 1964, readers all went out and became Ivy adherents. Parents and authorities, however, were hardly thrilled with a youth tribe of American style enthusiasts. The first strike against the Miyuki-zoku is that the guys — gasp! — would blow dry their hair. This was seen as a patently feminine thing to do.

More critically, the Miyuki-zoku picked the wrong summer to hang out in Ginza. Japan was preparing for the 1964 Olympics, which would commence in October. Tokyo was in the process of removing every last eyesore — wooden garbage cans, street trolleys, the homeless — anything that would possibly be offending to foreign visitors. The Olympics was not just a sports event, but would be Japan’s return into the global community after its ignoble defeat of World War II, and nothing could go wrong.

So authorities lay awake at night with the fear that foreigners would come to Japan and see kids in tight high-water pants hanging out in front of prestigious Ginza stores. Neighborhood leaders desperately wanted to eradicate the Miyuki-zoku before October, so they went to Ishizu of VAN and asked him to intervene. VAN organized a “Big Ivy Style Meet-up” at Yamaha Hall, and cops helped put 200 posters across Ginza to make sure the Miyuki-zoku showed up. Anyone who came to the event got a free VAN bag — which was the bag for storing your normal clothing during loitering hours. They expected 300 kids, but 2,000 showed up. Ishizu gave the keynote address, where he told everyone to knock it off with the lounging in Ginza. Most acquiesced, but not all.

So on September 19, 1964, a huge police force stormed Ginza and hauled off 200 kids in madras plaid and penny loafers. Eighty-five were processed at nearby Tsukiji jail. The kids got the message and never came back, and that was the end of the Miyuki-zoku.

Starting in 1945, Japanese authorities generally viewed all Western youth fashion as a delinquent subculture. Despite looking relatively conservative in style compared to the other biker gangs and greasy-haired rebels, the Miyuki-zoku were still caught up in this delinquent narrative. In fact, they were actually the first middle-class youth consumers buying things under the direction of the mainstream media. It was Japanese society that was simply not ready for the idea that youth fashion could be part of the marketplace.

After the Miyuki-zoku, however, Ivy became the de facto look for fashionable Japanese men, and the “Ivy Tribe” that followed faced little of the harassment seen by its predecessor. The Miyuki-zoku may have lost the battle of Ginza, but they won the war for Ivy League style. — W. DAVID MARX

As the Ivy League style swept across the globe. The British Modernist ‘Mods’ subculture adopted the clothing, modifying it into a very British subculture, with a new more aggressive edge. The Skinheads

Bracknell Skinheads 1970

W. David Marx is a writer living in Tokyo whose work has appeared in GQ, Brutus, Nylon, and Best Music Writing 2009, among other publications. He is currently Tokyo City Editor of CNNGo and Chief Editor of web journal Néojaponisme.